Happy Feast of Corpus Christi!

Around the year 750, in the city of Lanciano, Italy (then known as Anxanum), a great miracle took place involving a Eucharistic host. The “Miracle of the Lanciano,” is the oldest and greatest Eucharistic miracle which has been officially recognized as authentic by The Catholic Church.

Around the year 750, in the city of Lanciano, Italy (then known as Anxanum), a great miracle took place involving a Eucharistic host. The “Miracle of the Lanciano,” is the oldest and greatest Eucharistic miracle which has been officially recognized as authentic by The Catholic Church.

The First and Greatest Eucharistic Miracle

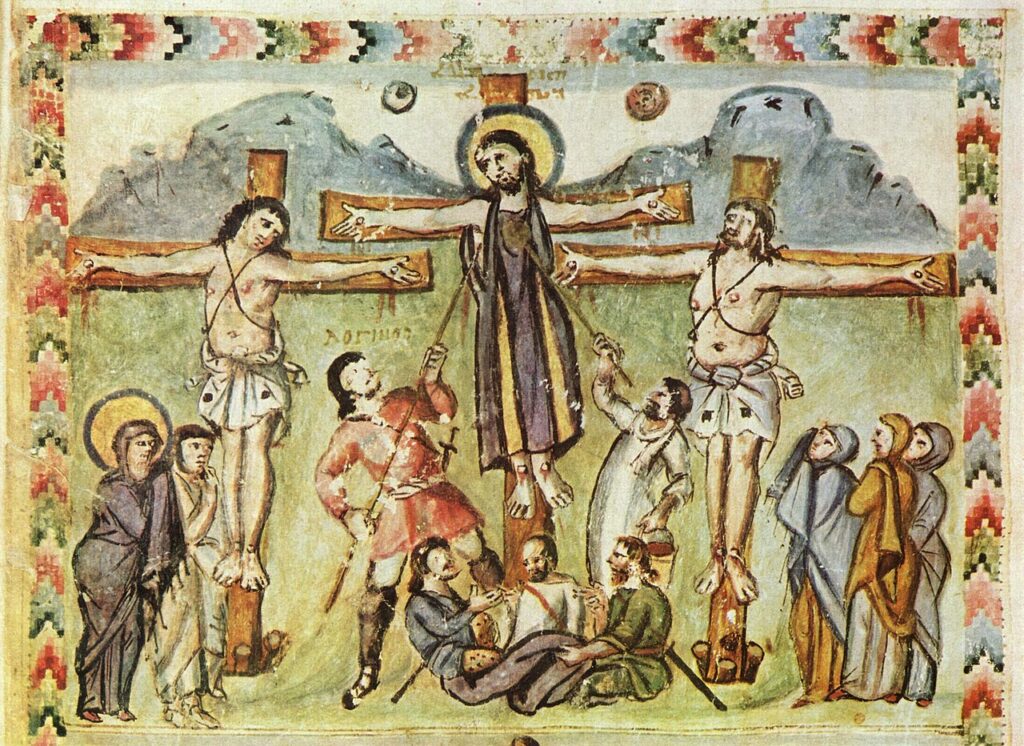

The miracle occurred during a Mass being offered by a certain Basilian monk, who was experiencing doubts about transubstantiation. After he had consecrated the Eucharistic bread and wine, they were transformed before his eyes into physical Body and Blood of the Lord. The monk was so moved that he wept. Those who witnessed the miracle confessed their sins to God and begged for his forgiveness.

News of the miracle was quickly spread by those who had witnessed it. After an investigation by the Church, this event was recognized as the first Eucharistic miracle, and the transformed bread and wine were kept in special ivory boxes.

Unfortunately, the original eyewitness accounts of this miracle, along with the details of the original investigation of it, were lost sometime prior to the 16th century.

What language was the Mass celebrated in?

“Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my body, which is given up for you.”

Was the miraculous Mass of Lanciano an Eastern-rite Mass said in Greek, or a Western-rite Mass said in Latin?

The Eucharist is central to the faith of Catholics, who believe that during Mass, the Eucharistic bread (the “host”) and the wine are changed into the Body and Blood of Christ (God the Son) by the priest’s words of consecration. These words, the words of consecration used by the priest at Mass, are the words of Jesus himself. Therefore, they are the words of God the Word, and the words of God have power. This mysterious change is known as “transubstantiation.” (An explanation of transubstantiation can be found here.)

At that time (the eighth century), before the Great East-West Schism, the Christian Church was not divided. There were different languages and rites in various places; but whatever language they spoke, or whatever rite they used, all of the bishops in the world were in communion with each other, and with the Pope.

The Mass at which the miracle of Lanciano occurred was said, as mentioned above, by a Basilian monk. The Basilian monks came from the eastern part of the Roman Empire, that is to say, the Greek-speaking part. In addition to speaking a different language, the Christians of the Eastern Roman Empire also used a different liturgy (or “rite”) when saying Mass.

When Mass is said in the Latin (or “Western”) Rite, the priest must use unleavened bread. In the Byzantine (or “Eastern”) Rite, however, leavened bread must be used. The miraculous flesh preserved at Lanciano is in the shape of an unleavened host, as used in the Western rite; therefore, we can be sure that the miraculous Mass of Lanciano was said in Latin.

Why were the monks of St. Basil in Rome?

In the Roman Catholic Church, there are many orders of consecrated religious, such as, for example, the Benedictines, the Franciscans (who are in turn divided into several different orders), the Dominicans, the Carmelites, and so on. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, there is only one, namely: the Order of St. Basil, which has remained virtually unchanged since it was founded in 356.

Unfortunately, some of the eighth-century Eastern Roman Emperors believed in the Iconoclast heresy, which holds that the making and venerating of icons is sinful. These emperors persecuted the orthodox Christians in the East; as a result, many Greek-speaking Christians fled to Italy. Among them were many Basilian monks.

St. Longinus, from which the town of Lanciano derives.

But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water. (John 19:34)

At some time (it is not clear exactly when), the town’s name was changed from “Anxanum” to “Lanciano.” The origin of the name “Lanciano” is not clear. One theory is that it is based on the Latin word “lancea,” meaning “lance,” in reference to the spear with which St. Longinus pierced the side of Jesus.

The miracle took place in a small church dedicated to St. Legontian (also known as St. Longinus) and St. Domitian. Who were Saints Longinus and Domitian?

According to legend, Longinus was the centurion who pierced our Lord’s side with a spear. It is said that he became a Christian after Jesus’ resurrection, and that he was later martyred. Longinus is said to have been born in the town of Anxanum (i.e., Lanciano), which is why it is natural that a church there would be dedicated to him.

As for St. Domitian, he is believed to have been a priest in the 6th century who fought diligently against heresy. Given their situation (fleeing from a heretical emperor), it makes sense that the Basilian monks in Italy would choose St. Domitian as their patron saint.

It is a fitting name for a town where a great miracle took place.

The Monk who had Doubt.

Around AD 700, there were Basilian monks in this church, which was then called the Church of St. Legontian.

One of the monks doubted whether the consecrated Eucharistic Host was really the Lord’s body, and whether the consecrated wine was really the Lord’s blood.

This monk began to say Mass. After saying the words of consecration, he saw the host become flesh and the wine become blood.

He showed it to all who were present and made it known to all.

Today, the flesh is still in one piece, and the blood is divided into five unequal parts.

They can be seen today in a certain Church of St. Francis.

An inscription in the chapel records that a certain monk was distressed because he could not believe in the presence of the Lord in the Eucharistic Bread, and that a miracle occurred in which the Eucharistic bread and wine were not only transubstantiated but also transformed, so that the Body and Blood of Christ were perceptible to the senses.

According to Father William Saunders, an ancient manuscript says that the monk “… was well versed in the learning of this world, but ignorant of the learning of God.”

From this short passage, we can picture the monk as a scholarly type of person who has done a lot of studying. “Ignorant in the sciences of God” probably means that he needed to learn about theology, and about how God wanted him to live.

This unnamed monk is remembered, not just as a priest who doubted, but as a priest who struggled with doubt. The fact that he struggled with his doubts, as opposed to simply shrugging his shoulders (as it were) and accepting them, is an indication of how serious he must have been in his faith. Like St. Thomas the Apostle, he did not proudly persist in his doubts, but humbled himself, and, finally, believed.

Another Miracle

A miracle occurred, and the Eucharistic bread became visible human flesh. The wine became a mass of five blood clots of different sizes, representing the five wounds Christ received during his crucifixion.

In 1574, a further miracle occurred: the five clots of blood, while different in size, were found to be all the same weight. Not only that, but the five blood clots put together weighed the same as each clot singly.

The phenomenon of the miraculous blood clot weights was not reproduced by investigations conducted by the bishops in 1637, 1770, and 1886; a study in the 1970s measured the weight of a single blood clot at 0.56 ounces (about 15.88 grams).

A Scientifically Proven Miracle

The relics were scientifically examined by the World Health Organization from 1970 to 1973. In 1981, the relics were re-examined using more advanced techniques.

The research and analysis team involved in the study included two doctors, a professor, and a physician, all specializing in human anatomy and physiology.

One of the researchers was Dr. Odoardo Linoli, professor of anatomy, histopathology, chemistry, and clinical microscopy and physician-in-chief of the hospital in Arezzo; another researcher was Dr. Ruggiero Bertelli, professor emeritus of human anatomy at the University of Siena .

The analysis of the flesh and the blood clots was performed according to scientific standards, and the findings were published.

Wine Transformed into Blood

The serum protein composition of the Lanciano clots was found to be the same as that of fresh human blood, and the clots contained minerals such as chloride, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, sodium, and calcium. The blood type of the Lanciano blood was found to be AB-negative.

People with the AB-negative blood type represent less than one percent of the population, making it a very uncommon blood type. On the other hand, the blood types of the Sudarium of Oviedo, the Sacred Tunic of Argenteuil, and the Shroud of Turin are all AB-negative.

Bread Transformed into Human Flesh

The investigation revealed that the altered Eucharistic Host was definitely flesh; in fact, it was human tissue. Specifically, it was heart muscle tissue, taken from the myocardium (the walls of the heart) and the endocardium (a membrane of fibrous elastic tissue covering all cardiac cavities). It was concluded that the flesh appeared to have been cut into a thin, round, uniform slice, which would have been possible only with the skill of a trained pathologist.

What was remarkable was that these samples of blood and flesh had been preserved in their natural state, still fresh after twelve centuries. The doctors who examined them testified that they showed no traces of preservatives. Professor Linoli emphasized after the re-examination that neither the blood nor the flesh was as if it had been taken from a corpse, but rather had the characteristics of fresh human flesh and blood.

More information on the scientific findings can be found at The Eucharistic Miracle of Lanciano – Historical, Theological, Scientific and Photographic Documentation.pdf (keepingfaith.me)

The Church of the Reliquary

It is believed that the miraculous relics were kept in the church of Lanciano by the Basilian monks until their departure in 1175. At the end of the 12th century, however, the church and monastery were abandoned. With the approval of Pope Innocent III, the church was handed over to the Benedictines. The diocesan bishop then transferred it to the Franciscans.

The Franciscans who inherited the church building found that it had been devastated by centuries of earthquakes; in 1258, a new Franciscan church and convent was completed on top of the existing church.

The relics continued to be kept on the altar of that new Franciscan church until 1636, when they were moved to the Valsecca Chapel. Then, in 1902, they were moved to a new altar in the church, where they have remained ever since.

Here is the link to the St. Francis Church website.

Santuario del Miracolo Eucaristico – Dominus meus et Deus meus

The Doubting Basilian Monk, Who also Represents Each of Us

In the words of Father Silvio Di Giancroce, a guide at the Lanciano church, “That doubtful Basilian monk who was the occasion of the Miracle of Lanciano represents each one of us.”

In his sermon on the Eucharist, a priest explained that “it is not a mortal sin to doubt the presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist, even though we want to believe in it, but it is a mortal sin to deny it outright.”

According to the Catholic News Agency by Joe Bukuras (Sep 29, 2023 ), about two-thirds of Catholics in the U.S. believe that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist. A Eucharistic revival is beginning to take place. On the other hand, that means that the remaining one-third of U.S. Catholics do not believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The Church’s rules are clear: If you do not believe, you must not receive Communion. To do so would be a mortal sin. I sincerely hope that the unbelieving Catholics of the world are not defiling their souls with unworthy communions.

When I am busy with my daily life, I tend to give priority to what I can see. I feel that my mind is not focused on God. Jesus, God incarnate, left us not just a memorial, but his true bodily presence in tangible form, in His Eucharistic bread and wine. The miracle of Lanciano shows us the truth of the Eucharist: it is nothing less than the tangible body of God. I intend to reflect on this miracle of the Eucharist so that I can live a God-centered life as much as possible.

Image: Reliquary displaying the relics of the Eucharistic miracle of Lanciano (Wikipedia)

Sources:

The Eucharistic Miracle of Lanciano by Fr. Nicola NasutiOFM Conv.

Church of San Francesco (Eucharistic Miracle) – Lanciano (wikimapia.org)